In Praise Of Hayek's Masterwork

Friedrich von Hayek first published The Road to Serfdom in 1944. His book was subsequently popularised by a condensed version in The Reader’freed

Why personal freedom is important and the threat to it

Destroy personal freedom, and ultimately the state destroys itself. No state succeeds in the long run by taking away freedom from individuals, other than those strictly necessary for guaranteeing individualism. And unless the state recognises this established fact its destruction will be both certain and brutal. Alternatively, a state that steps back from the edge of collectivism and reinstates individual freedoms will survive. This is the theoretical advantage offered by democracy, when the people can peacefully rebel against the state, compared with dictatorships when they cannot.

Nevertheless, democracies are rarely free from the drift into collectivism. They socialise our efforts by taxing profits excessively and limiting free market competition, which is the driving force behind the creation and accumulation of personal wealth and the advancement of the human condition. At least democracies periodically offer the electorate an opportunity to throw out a government sliding into socialism. A Reagan or Thatcher can then materialise to save the nation by reversing or at least stemming the tide of collectivism.

Dictatorships are different, often ending in revolution, the condition in which chaos thrives. If the governed are lucky, out of chaos emerges freedom; much more likely they face more intense suppression and even civil war. We remember dictatorships through a figurehead, a Hitler or Mussolini. But these are just the leaders in a party of like-minded statists.

When comparing dictatorships to democracy we think in terms of black and white, which allow one to express concepts clearly. But reality always comes in shades of grey. Far from being always bad, dictatorships can be successful if they permit individuals to retain the freedom to improve their lives and accumulate the benefits of their success. This is the freedom to compete, make and keep profits. A dictatorship on these lines is mercantile, offsetting the absence of political freedom by allowing personal freedom to develop within the confines of state direction. This is the current situation in China and Russia.

Modern democracy is usually flawed, a cover for the state to rob Peter to pay Paul to the point where Peter is impoverished or refuses to play the game and both the state and Paul are then bereft of funds and purpose. This is the condition to which Western democracy has evolved in modern welfare states. We can all sympathise with the underlying concept: there are those in life who through circumstances fall on hard times, and if they are given a helping hand, will eventually benefit society as a whole. But it becomes counterproductive when it discourages the individual from returning to productive society. Not only is the individual’s contribution to society lost, but he becomes a burden upon it.

For its revenue the state relies on the production of many Peters. The consequence is even more Pauls. The cost of welfare increases with its scope. It becomes welfare for all, with everyone having a right to it. Each Peter ends up funding ninety-nine Pauls. This is Mediterranean Europe today, and perhaps to a lesser extent Britain and America.

With compulsion, the state no longer protects the rights of the individual. Democracy has permitted the modern state to evolve into a separate entity no longer the servant of the population.

The cross-over between democracy and dictatorships

In economic terms, a high-spending statist democracy is indistinguishable from a dictatorship. Instead of promoting free markets, both create the conditions where commercial success is achieved by influencing the government. The difference is in the form this corruption takes. In the case of a high-spending democratic government, obtaining control over the regulatory process is vital for a business to secure market advantage and keeping competitors at bay. In a dictatorship corruption is usually more direct.

So long as free markets are not completely prohibited by the state, this crony capitalism thrives. From banks to pharmaceuticals, it is the way business is done today. It angers ordinary people, who are then persuaded by support-seeking politicians that big business is motivated by profit without social consideration, and that the socialising policies of the government are the solution. As the Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek put it, the people are now embarking on the road to serfdom.

The Road to Serfdom was about the cross-over between democracy and dictatorships. Hayek wrote his famous book in 1942-44 (it was first published in 1944), drawing on the example of Germany’s contemporary experience. He showed how the organisation of a war-time economy by the state, in Germany’s case the First World War, becomes a template for central planning in peacetime. While Hayek showed that a government’s central planning of a war-time economy forms the template for peacetime central planning, peacetime planning also develops on its own.

The planners always promise a utopian view of the future. People are easily persuaded that planning for the benefit of everyone is an advancement on the sole motivation of profit. However, disagreements arise on what plan is best, reflected in the split between different political parties. The planners from different factions all have plans but no unity of purpose. The people disagree as well. What is needed is government propaganda to dispel disagreement and unite the people behind the government’s preferred plan.

The propaganda machine goes into action. Information is selectively fed into it to obtain public support for government policies. Statistics are manipulated to promote success and obscure failure. Any reporter who does not cooperate with the government line is excluded from the planners’ briefings, giving his rival journalists an advantage. He conforms. The use of the press to support state planning becomes increasingly important in covering up its failures.

The failures of central planning proliferate. The propaganda machine cannot cover up all the evidence, and the planners respond with even more planning, yet more suppression of personal freedom. There is no turning back. They argue it is not their fault, but the fault of the people failing to cooperate and comply with government policies. They argue that the people are uneducated and not responsible enough to have a say in central planning. What’s needed is someone strong enough to force the plans through. At the same time, ordinary people want a strong man to kick out the useless bureaucrats and make the plans work.

A new leader emerges. The democratic establishment see his function as temporary. When order in the planning process is restored, he will no longer be needed. But this is the cross-over point between democracy and a dictatorship. He is a Chavez, a Putin, a Lenin, a Mussolini, a Hitler. It was the latter fascists that were perhaps freshest in Hayek’s mind, but he was also fully aware of Lenin and Stalin.

Not all strongmen emerging from the chaos of planning failures turn out to be a Lenin or a Hitler. Those who follow a mercantilist path, contemporary examples being Russia’s Putin and China’s Xi, are careful to allow individuals the freedom to run their affairs without the heavy hand of the state. But they are also careful not to let democracy undermine their control: the people cannot have both and opponents to the state are ruthlessly dealt with.

Anyone intending to be Hayek’s strong leader promises to make order out of bureaucratic chaos. Those on the far left (in the UK, Corbin and McDonnell, in the US Bernie Sanders) believe the political solution to growing economic chaos is to take collectivism to a higher plain. Free-marketeers are derided by the planners as being antisocial, profit-seeking right-wing extremists. If Corbin and Sanders are to succeed in their desire for office, they must wish for an economic or political failure that damns capitalism and will see them swept into office.

Then what happens?

We will continue with Hayek’s narrative. The new leader uses the chaos that led to his election as the pretext to consolidate his power.Opposition is not permitted, because it restricts the leader’s ability to resolve matters. With dissenters excluded, democracy becomes little more than a propaganda exercise. The leader only permits people to vote for him and his party. To encourage national unity in the face of deteriorating economic conditions, a minority in society is made a scapegoat. With Hitler it was the relatively prosperous Jews. Corbin’s apparent dislike of Britain’s Jewish community is striking a raw nerve.

In truth, we cannot forecast what class or creed will be tomorrow’s scapegoat. It will depend on the nation, the strongman and his immediate supporters, their religious beliefs perhaps, and how rapidly planning undermines the economy. Wealthy communities with wealth for the state to acquire will be at risk. But one thing is for sure, increasing numbers of secret police will be deployed to supress all opposition. Dissent is dealt with ruthlessly.

Hayek went on to detail what we have subsequently seen, in Africa with Mugabe, in Venezuela with Chavez and then Maduro. These are the most egregious of many contemporary examples, mainly confined to developing nations. Now the mature economies in Europe, of America and Britain are drifting that way.

The current regimes in Russia and China are different, having become post-Hayekian political economies. They are mercantilist in nature. Individualism is allowed to flourish, with collectivism limited. But for these regimes to survive a wider global Hayekian transition from democracy to a lasting mercantile dictatorship, they will need to give up money-printing and return to sound money. This is our next topic.

Sound money is central to personal freedom

It has been several generations since individuals have been free to choose their own money, and people have become conditioned to state currencies. However, total control of money issuance gives enormous powers to the state which it exercises at the expense of ordinary people. In the past, the state had to face the limitations of sound money. Sound money puts a brake on the ambitions of the state. A state currency can be issued at will, which means that in nominal currency terms the potential transfer of wealth to the state through monetary inflation is infinite.

All recorded hyperinflations have been with state currencies. No politician can resist the temptations of the printing press. Politicians even justify currency debasement, saying it benefits the people by stimulating production and consumption. It becomes fundamental to the planning process, the management of the business cycle. What is not mentioned is the existing stock of money, being debased, buys less. And it is not a business cycle any more, if that ever existed, but the consequences of a cycle of credit and monetary expansion.

By issuing currency, the political class finances its ambitions without the need for raising taxes. But since there are no distinguishing features on new money compared with the old (and today it is mostly electronic anyway), the users of state currency are none the wiser. Inevitably, when more money chases the same quantity of goods, its purchasing power declines, reflected in rising prices. Governments then supress the symptoms of monetary inflation by regulating prices, or by corrupting the statistics. But so long as markets exist, these attempts always end in failure.

It is this failure to control the effects of monetary debasement that invalidates the concept of the state issuing its own currency. This is why people transacting with each other naturally select gold and silver as money – they can be sure of its value.

The monetary role of the state originally was to issue recognisable coins in gold or silver of uniform weight. When banks began to issue notes backed by gold deposits, central banks soon took over that function. They then swapped the commercial banks’ gold for balance-sheet deposits at the central bank on the promise the deposits would be repayable in gold.

Acting on behalf of the state, this was how central banks monopolised the national stocks of gold. In time, they progressively removed the promise to honour payment in gold. In the United States this happened in two steps. Ordinary people and corporations lost the freedom to own gold in 1933, then in 1971 the Americans ceased gold payments entirely.

The Americans then began a campaign to remove gold from the world’s monetary system, promoting the dollar as its replacement. The motivation was clear: the American government took to itself unlimited power to issue fiat dollars. It has used this power freely ever since.

The power to issue unlimited amounts of fiat dollars will eventually destroy the currency. The time taken for that destruction is not under the control of the government, but of its users, both domestic and foreign. We know the dollar will continually lose purchasing power so long as it is a pure fiat currency. We can also be reasonably sure that the speed of its attenuation will accelerate, particularly when the US Government attempts to finance its escalating costs in a future credit crisis. And we know a credit crisis will happen as a consequence of aggressive monetary expansion earlier in the cycle.

Every state has a fiat currency. Every state is convinced of the benefits of monetary inflation. Every fiat currency is in danger of obliteration. And as the collapse of fiat currencies progress, populations will become increasingly discontent with their planners. The demand for strong leadership, by which we mean successful planners and their parties, will see many of them elected. Most will become increasingly tyrannical. Only very few will respect the individual and personal freedom.

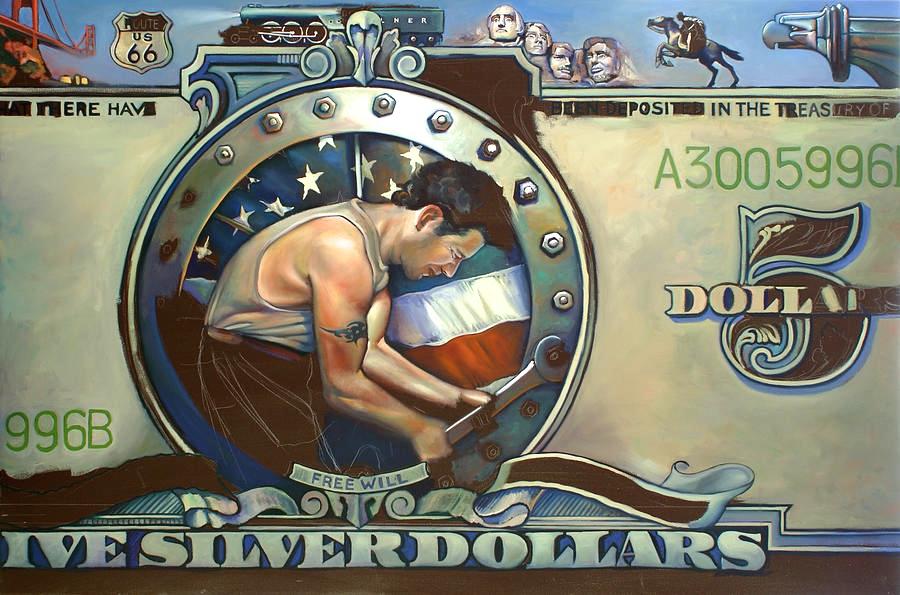

Money has become central to the Hayekian road to serfdom and the destruction of free markets and democracy, which is bound to lead us all into statist servitude.

Different outcomes for different states

Europe

The developed countries most blind to the dangers of losing democracy by drifting into totalitarianism appear to be in the European Union. The invention of the euro has, temporarily at least, prevented the weaker member states from drifting into hyperinflation and government bankruptcy. Political discontent is mounting in these nations, and the Brussels super-state is supressing democracy. The centralisation of the currency has taken away from these states their political control over the currency as a means of inflationary financing, but that is now vested in a centralised system. Their economic collapse and drift into extremism has only been delayed.

The cost to the rest of the Europe is a monetary hyperinflation of the euro: it has already started, only prices have yet to reflect it. The Brussels strongmen holding it all together are doing so by supressing dissent, just as Hayek predicted. Instead of a single identifiable leader, they are hidden within the entire Brussels bureaucracy. It is, perhaps, an interim arrangement, leading to the chaotic conditions of a financial and economic crisis, from which a true European leader will hope to emerge. If you want a role model for the EU, look no further than Bismarck, who unified Germany in the nineteenth century, and then employed inflationary financing before the First World War.

United Kingdom

The British electorate voted in a referendum to escape from their politicians’ grand European scheme. It has succeeded in exposing the level of separation between the state’s planned objectives and the wishes of its people. Brexit has also shown how the state strongly resists democracy. This has discredited the Conservative government, enhancing the hopes of a Marxist clique in the Labour Party. Messrs Corbin and McDonnell are actively plotting for the chaos that will lead them into power. They then hope to follow in the footsteps of Lenin, Castro and Chavez towards a communist utopia.

United states

America is fighting decay. The wise strategic planners of the past have been replaced by men in the deep state who above all fear decline. The public rebelled against the collectivism of the Democrats by electing President Trump, but it is becoming clear the public has only swapped one statist for another.

Trump quickly fell in with the deep statists and their war games. This is another central proposition of Hayek’s road to serfdom. But for Trump and his administration, war, tacit or otherwise, is not being pursued successfully and his trade protectionism risks driving America into a deepening recession.

A president elected by the people for the people and not the established state is turning out to be increasing dependent on monetary inflation, the transfer of wealth from the people to the state. Trump has tried to reverse the trend into planning and socialism, but basic economics tells us he has made the government’s future funding crisis worse. By the laws of unintended consequences, he has increased the likelihood of a future president returning to the path of collectivism.

Japan

Japan appears to be broadly immune to these Hayekian influences. Despite monetary inflation, people increase their savings, reducing the impact on prices and guaranteeing a trade surplus. For the moment, Japan is blessed with a society which is ordered and does not rebel. The conditions that lead to a dictator do not yet appear to be present.

Asia’s two super-powers

Over thirty years ago, the dictatorships of China and Russia faced a political and economic collapse and have emerged as mercantilist dictatorships. If they are wise, they will soon discard the inflationary practices of the West and return to sound money before it undermines their mercantilism. If they do this and let free markets work, they will increase their economic strength and improve the standard of living for their ordinary people. The leadership of these two nations show signs of understanding this point.

Conclusions

With Russia and China being the only two major economic powers in their current form capable of surviving the political chaos that lies on our road to serfdom, the creed of democracy in government will probably die for many generations. Eventually, we could be asked to choose between individual freedom and democracy, the model currently employed by Russia and China. The proposition will be that only a strong unaccountable administration can control the welfare demands of the majority. We will be told to get on with our lives and not to interfere in politics: we can only vote for a one-party state.

It would be a cultural shock, coming after the collapse of fiat currencies. But as we are seeing increasingly, Western democracies are little more than a sham. But it is difficult to see that the systemic and economic crisis, which we all face, will eventually allow us to return to both democracy and personal freedom.

That was Hayek’s underlying point in his Road to Serfdom.